02.02.2014

WHAT IS OUR COUNTRY?

The UKIP poster campaign implores the people's army to 'take back control of our country'. The escalator breaching our beloved white cliffs of Dover was described by Mr Farage as 'the most powerful image of the entire European election campaign'.

What is he alluding to?

The white cliffs of Dover have iconic status in the British psyche. They are linked with the Battle of Britain, when the RAF heroically defended these shores against the might of the Luftwaffe during the summer and autumn of 1940. In 1942 the force's sweetheart Vera Lynn sang 'There'll be bluebirds over the white cliffs of Dover'. The song was a message of hope and reassurance; everything will turn out alright and we'll get our country back again soon.

But all is not what it seems. The emotional tugs upon which the UKIP poster relies should be questioned.

The white cliffs of Dover have a shared geology with the white cliffs of Normandy — we just happen to be separated by 3.75 miles of water from the European mainland. In fact, we are so close that cliff top walkers in Kent who use their mobile phones are greeted with a 'Welcome to France' message.

Ten miles further down the coastline you will find Capel-le-Ferne and the Battle of Britain Memorial with a roll call of nearly 3,000 brave aircrew who took part. 'The Few' as Churchill called them, include 574 pilots from other countries — notably from Poland. It was the Polish 303 'Kościuszko' fighter squadron that shot down more enemy aircraft than any other Allied squadron during the Battle of Britain. Flight Lieutenant John Kent of 303 squadron said of the Polish Wing, "Britain must never forget how much she owes to the loyalty, indomitable spirit and sacrifice of those Polish fliers. They were our staunchest Allies in our darkest days; may they always be remembered as such!"

And what of 'the bluebirds over the white cliffs of Dover'? This most popular Second World War song was penned by two Americans who either didn't know that the bluebird wasn't a European species or if they did, perhaps it was their way of suggesting that Britain would get their country back under the protection of American birds in the guise of the US Air Force. These 'bluebirds' still fly over the white cliffs of Dover today.

So what is 'our country'?

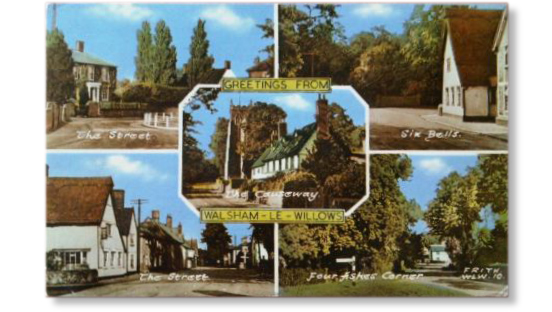

I recently went for a walk through the picture-postcard Suffolk village of Walsham-le-Willows. Nothing could be more quintessentially English; thatched cottages, a church with knapped flint walls, a clear stream winding its way through a village surrounded by lush hedgerows and green fields.

My amble took me up an old cart track. The hedgerow to my left is thought to be more than 700 years old. To my right was Mill Field, once cultivated by village families who each had a small strip of land. Today, the 14th-century strip farming has been replaced by a giant field of barley.

Historians know a lot about Walsham-le-Willows because written records still survive from as far back as the Norman Conquest. A tax record from 1283 lists 90 villagers who reared sheep, cattle, horses, pigs, and chickens. Wheat, barley, oats, rye, beans and peas were also grown, timber came from the nearby woods, tenants grew their own crops in open field strips and grazed their animals on common land. The village thrived until the Black Death struck in 1349, ending the feudal system. Land was turned over to pasture and peasants quickly became tenants of the manor. By the early 1600's Walsham-le-Willows had its yeomen with their own homes and holdings. Raphe Margery raised a troop of 113 local men to fight for the Parliamentarian cause in Cromwell's New Model Army. Other inventories from 1625 describe local tenants as hemp weavers and whitesters (bleachers). Throughout the 1700's the village began to grow again and by 1851 it had reached its pre-plague numbers. Houses were timber and thatched, accommodating several families. The last remaining common grazing land was enclosed in 1819. A tithe map from 1842 shows hundreds of small arable and pasture fields defined by miles of hedges. By this time the village had a milliner, thatcher, baker, plumber, cooper, gun-maker, brewer, maltster, smith, shoemaker, saddler, and a rope-maker. The Martineau Family (now the major landowners) financed the building of the village school and also built Jacobean-style estate cottages for their workers. Village life changed dramatically after the two World Wars. Mechanised farming meant less work for farm labourers and many families moved to the towns to seek employment and housing. Today, Walsham-le-Willows has a population of nearly 1,200 people, with 95.3% of residents having been born in the UK.

So Walsham-le-Willows is a very old English village, shaped by English history. Let's look at this English history a little more closely.

The Norman Conquest was led by William, Duke of Normandy. Rewarding his Norman, Breton and French troops with land, he systematically dispossessed all Anglo-Saxon landowners. The Doomsday Book of 1086 states that Walsham Manor was held by Robert de Blund from Guisnes, near Calais.

Domesticated animals such as sheep were probably brought to Britain from mainland Europe by Neolithic settlers. Grain crops, beans and peas are all from the Middle East and Asia.

The Black Death is thought to have originated on the plains of central Asia around 1338. It spread along the Silk Road, reaching the Crimea in 1347, and from here the virulent plague swept through Europe, reaching England by 1348, and killing half the population of Walsham-le-Willows within the year.

Raphe Margery held nonconformist beliefs which led him to be excommunicated from Walsham church in 1635 by the Bishop of Norwich. Margery's theological impasse had its origins in Europe with the Calvinists seeking church reform. As a captain in Cromwell's New Model Army, Margery inadvertently helped bring about a Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland when Cromwell assumed powers as Lord Protector. The forging of a commonwealth (a political community for common good), has Icelandic / Norwegian and Polish / Lithuanian antecedents.

More plants from overseas; hemp grown for rope and canvas making came to Britain from Asia. The water reeds used for the picturesque thatched roofs of Walsham-le-Willows have traditionally been harvested in East Anglia. However, it is estimated that more than 80% of water reeds now used for rethatching in the UK are now imported from Turkey, Eastern Europe, China and South Africa.

Remarkably, there are 62 pre 1700 timber-framed houses still surviving in Walsham-le-Willows. Many homes were named after their tenants. During the 15th Century Deyes Cottage (above) was inhabited by the cooper Richard Deyes. He left in 1489 to go on a pilgrimage 'over the sea'. The building's medieval timber frame is hidden beneath an exterior render and during Deyes' time it would have had a thatched roof. Today, it has a pantile roof. These 's' shaped interlocking clay tiles came from the Netherlands during the 17th Century. The tiles were used as ship ballast and were replaced with a cargo of English wool for the return journey.

My walk finished at the village bowling green. As I peered over the hedge to admire the orderliness of the green, the ditch, and the bank (the heights of which are all precisely regulated using an 18th century French millimetre unit of measuring), I thought about the bowls made of lignum vitae. This dense hardwood comes from the Caribbean and is also used for cricket bails, croquet mallets, and for skittles. Traditional British sports all seem to rely on some vital overseas component.

'Our country' is clearly not what Mr Farage imagines it to be; European thinking has always influenced our religious beliefs and swayed our governments, and what we think of as the English countryside is really a smorgasbord of arrivals from afar. The white cliffs of Dover are not a defensive wall against Europe but our link with Europe, 'The Few' who defended 'our country' also included citizens of other countries, and the post-war stability we continue to enjoy comes from strategic security alliances made with Europe and other world partners, like the Americans. This is 'our country'; connected to the rest of the world, quietly absorbing the richness of the world, and then making it our own — like our national flower, the rose. That's another plant that made it here from Asia.

My walk through the quintessential English village of Walsham-le-Willows made me think about the benefits of reading the real landscape of 'our country'. For the moment, it is far more informative than the current political landscape.

Ian Chilvers

![]()